Schools Should Consider Multigenerational Households in Reopening Plans

Over 700,000 Californians Live in Multigenerational Households

It is imperative for school and political leaders to keep in mind that not every student lives in a nuclear family—i.e., with two parents and/or siblings—or, regrettably, in stable housing. This fact is especially significant during the COVID-19 pandemic given the difficulties and complexities of home learning environments, should remote learning persist, and given disparate risks of virus transmission in diverse communities and households, should schools reopen. Public health researchers shed light on the role of varied household and family structures on preferences for sending students back to school in a June 2020 survey, finding that the presence of a “medically vulnerable” person in a household was a positive predictor of whether a respondent planned to keep their student out of the classroom in the fall. In light of the positive relationship between risk of serious complications from COVID-19 and age, students living with elderly individuals comprise a significant population who might experience detriments to learning (e.g., by not returning to the classroom) and/or threats to the health and safety of themselves and their family members.

California is home to more than 700,000 people living in multigenerational households, which are documented by the Census Bureau as households where at least one grandparent lives with at least one grandchild. Using American Community Survey 5-year estimates from 2018, we estimate that California school districts serve 112,000 students living in multigenerational households, with some such students in nearly every district.

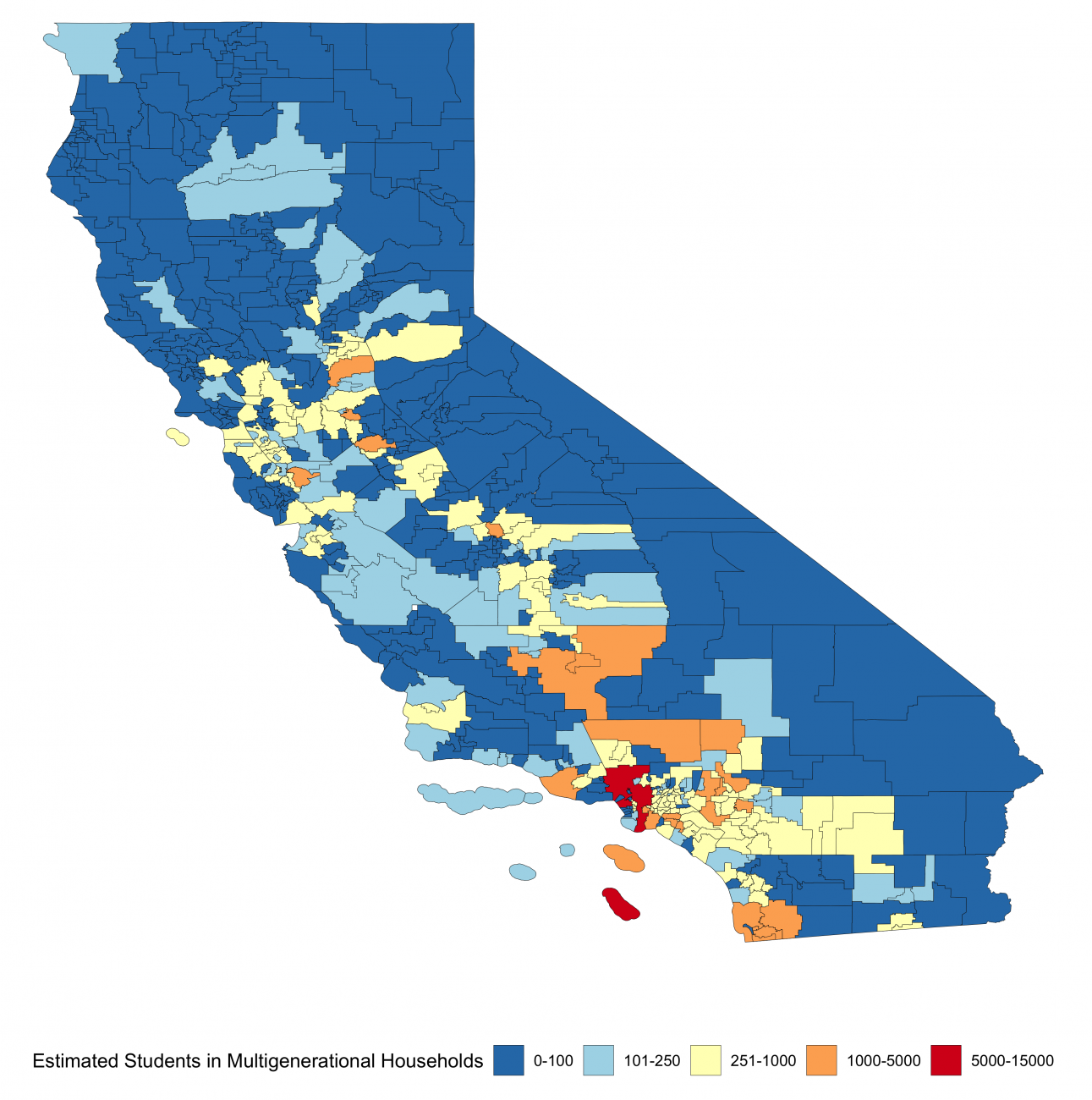

Figure 1. Estimated Number of Students Living in Multigenerational Households in California School Districts

Note. We estimated the number of students living in multigenerational households in a school catchment area by multiplying the estimated number students enrolled in public school by the estimated proportion of households in the district that contain at least one grandparent living with at least one grandchild.

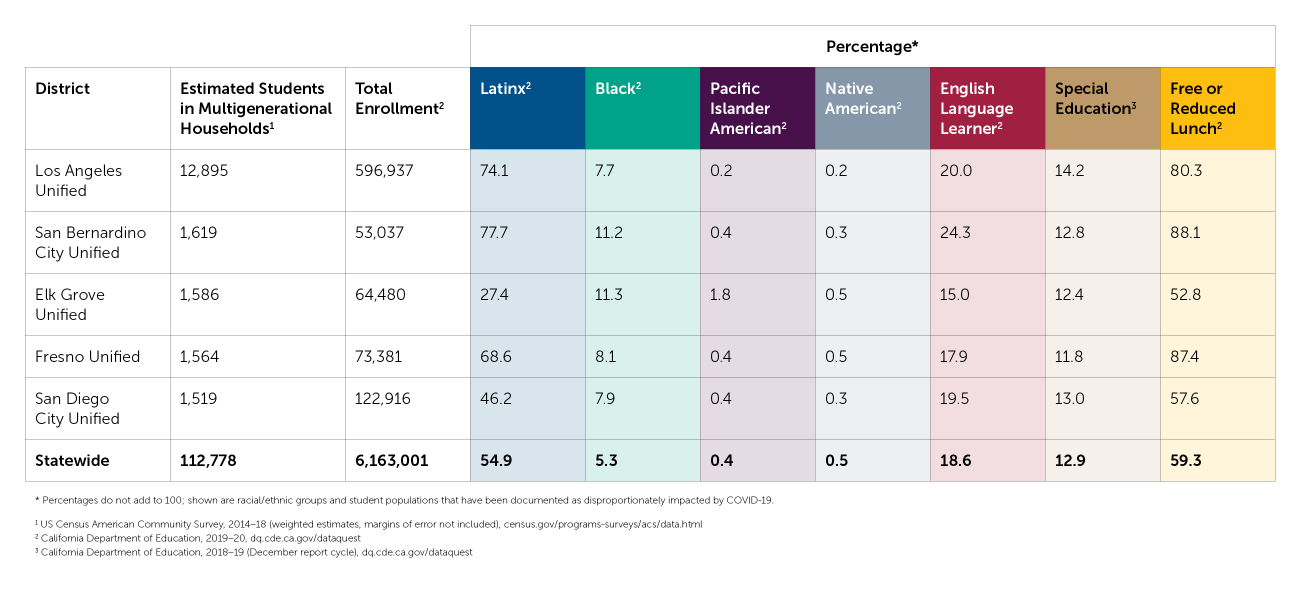

Table 1 highlights the socioeconomic and educational compositions of the top five districts serving the highest number of students living in multigenerational households. In the district with the largest proportion of such students, San Bernardino City Unified, over 3 percent live in multigenerational households compared to 1.8 percent statewide. While the data do not show the demographics of these specific students, we can extrapolate from the demographics of the district overall: San Bernardino serves a much higher proportion of Latinx students (77 percent) than the state overall (55 percent) and a higher proportion of low income students (88 percent in the district compared to 59 percent statewide), suggesting that multigenerational households there are more likely to be low-income and/or Latinx households.

Table 1. Characteristics of Select Districts Serving Large Populations of Multigenerational Households

Students With the Highest Level of Need May Be Reluctant to Return to School Buildings

Districts Can Mitigate Risks for Students and Families

Tens of thousands of California public school students live in multigenerational households. As parents, grandparents, and guardians in those households are more likely to keep their students out of school during the pandemic, districts should work to identify these students and offer additional resources that mitigate risks to their and their families’ health (e.g., creating small, physically-distanced learning cohorts; adjusting student arrival and departure times; making outdoor class space available) while making sure that student learning needs are met (e.g., prioritizing in-person attendance for students with special needs; providing adequate technology resources; ensuring that students learning from home have remote options for one-on-one and small group support). To that end, policymakers can use the information presented here to identify districts that serve a large number of multigenerational households and make additional funds available to meet the demands of serving those students.