The District’s Role in Community School Development

- Home

- Publications

- The District’s Role in Community School Development

Summary

California is prioritizing equity in education post-COVID-19 by investing in community schools. Districts have an important leadership responsibility to develop the conditions, capacities, and resources for effective, sustainable community schools. Specifically, districts must strengthen system-level supports and infrastructure to ensure sustainable resources, shared governance, robust and usable data systems, and organizational learning and improvement. The district can also support community school coordinators, strengthen data access and sharing, identify and celebrate successful school-site practices, and scale innovations. By taking a cohesive, districtwide approach to community school implementation and sustainability, district leaders can help ensure the success of community school transformation in their districts.

Introduction

As California emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic, there is renewed urgency for understanding and addressing persistent challenges of equity in education. California has seized this moment to invest in strategies that connect the evidence behind the science of learning and development with the demand of educators and community partners to foster high-quality, nurturing, and equitable learning environments. The legislature has made significant investments in community schools as a way to redress historic inequalities and support whole child education both in and out of the classroom. The $4.1 billion budget allocation provides an opportunity for preK–12 public schools across the state to plan and implement community schools through the California Community Schools Partnership Program (CCSPP).1

To support implementation of community schools statewide, the California Department of Education has approved a framework2 that draws on a community-engagement feedback process, the science of learning and development, and a growing research base on community schools. CCSPP funding is being awarded at the district level, with planning grants centrally focused and implementation grants primarily passed through to school sites. In both cases, district leaders have an important role to play in applying for the funding and supporting implementation at multiple school sites across the district. This brief provides guidance for district leaders on approaches to shifting their own leadership to support flourishing community schools. We draw heavily on existing research on Oakland Unified School District (OUSD), which has been operating community schools for more than a decade. In 2011, OUSD became the first full-service community school district in the country.3

What Is a Community School?

Community schools are often misunderstood as student support “programs” or “models” that a school or district may choose to implement, especially to target underresourced and academically low performing school sites. Others conflate community schools with co-located services (e.g., health clinics, food pantries, afterschool care, and family resource centers). Although many community schools do include integrated student and family support services, the ad hoc addition of services to a school site does not necessarily make for a community school.

Rather, a community school strategy commits to a comprehensive teaching and learning environment that educates the whole child; strategically leverages partnerships from within the community; and engages student, family, and community voices in shaping a vision for student success and school priorities. There is not one singular “model” of a community school, as all community schools reflect the diverse communities they represent and serve.

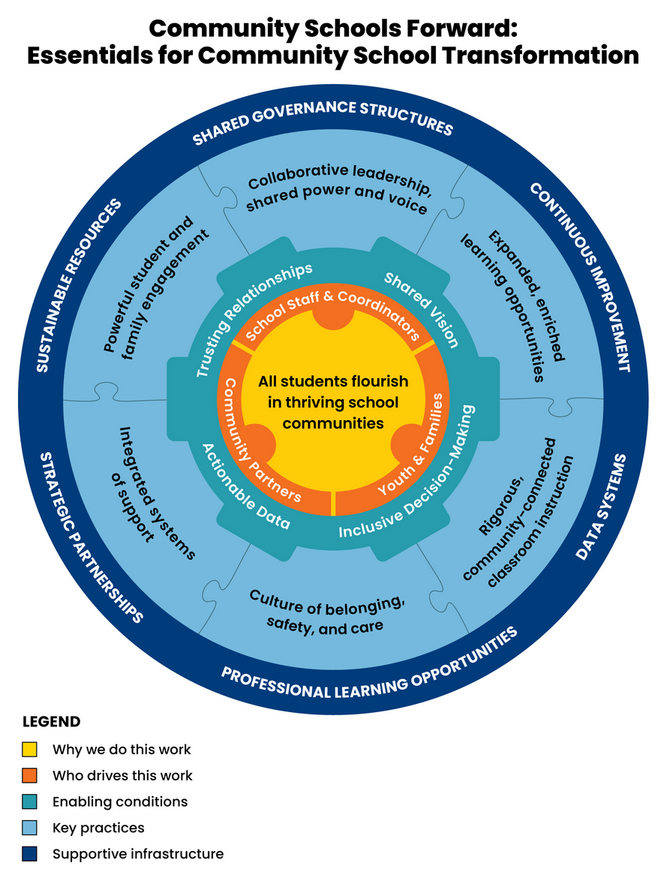

In 2021, four organizations—the Brookings Institution, the Coalition for Community Schools, the National Center for Community Schools, and the Learning Policy Institute— convened the national Community Schools Forward task force to build consensus on defining, understanding, and measuring successful implementation of community schools. Through engagement with more than 1,500 educators, scholars, researchers, and other stakeholders, the task force developed a shared definition and framework4 that articulates the essential elements of a fully implemented community school, including the why, who, and how (see Figure 1). This framework actively engages the four “pillars” of community schools, identified in an earlier report from the Learning Policy Institute,5 and repositions those pillars as part of an integrated strategy for school transformation. This brief focuses on the dark blue “supportive infrastructure” ring that encircles the wheel and the district leadership practices that can advance community school transformation.

Figure 1. Essentials for Community School Transformation

Source. Community Schools Forward. (2023). Framework: Essentials for community school transformation. learningpolicyinstitute.org/project/community-schools-forward. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

What Is the District’s Role in Community School Development?

Community schools have often been implemented on a site-by-site basis as localized endeavors or as small pockets of innovation within larger district systems. Little attention has been paid to the district-level infrastructure and support needed to develop and sustain community schools at scale. As the strategy becomes more widespread, districts are identifying their roles in creating and sustaining the infrastructure that supports the development of community schools. In this brief, we describe 14 practices that leaders in community school districts can implement to foster and develop community schools, whether leaders are starting with a few select schools or strengthening strategies so that all schools in the district operate as community schools. These practices fall under the six aspects of supportive infrastructure necessary for community schools: shared governance structures, strategic partnerships, professional learning opportunities and continuous improvement, data systems, and sustainable resources.

Shared Governance Structures

Collaborative leadership and shared governance are at the heart of the community school approach. Central to both is a collective vision of student success based on “the rich culture, history, geography, and identity of each school community and what they want to be true for their children and families.”6

Facilitate a collaborative visioning and planning process. One of the most important functions of a community school district is facilitating a collaborative visioning and planning process that includes students, families, educators, community partners, and municipal agencies. Many districts may already regularly be doing some form of collaborative visioning and goal setting as part of their accountability requirements. For example, in California, the Local Control Funding Formula requires districts to engage in a collaborative planning process with students and families to identify district goals and priorities. This process has the potential to engage a wider range of municipal organizations and community-based organizations (CBOs) at scale (e.g., city government, the local health system, or a nearby community college), which can provide input, context, and access to resources across the district. A districtwide engagement and planning effort has the potential to access a more coherent picture of community assets, aspirations, and priorities, highlighting areas of similarity and divergence. Rather than amassing multiple site-level visioning and planning processes that may result in either several potentially conflicting plans or one overly broad plan, a districtwide process can create a shared foundation for specific community school sites to build on, adapt, and individualize. This type of deep engagement usually requires substantive administrative capacity; when the district takes on this responsibility, some of the administrative burden for school sites is alleviated.

Spotlight on Practice

In 2010, OUSD kicked off its community school initiative with an 18-month strategic planning process involving 14 task forces and more than 3,500 participants. The result was an in-depth strategic plan—Community Schools, Thriving Students—that set the district’s direction for the next 10 years, despite several changes in superintendents during the first 7 years.

Build site-level capacity for collaborative leadership and decision-making. Many school and district leaders recognize the importance of collaborative leadership, but they often struggle with meaningfully engaging the leadership of students, families, and community partners.7 The district plays an important role in scaffolding both the structures and mindsets to support collaborative leadership and shared decision-making with educators, students, families, and community partners to create schools that belong to the community. This support may include providing templates and tools to schools, such as facilitation guides and resources to make school-site council meetings more inclusive and collaborative. Districts can also commit to practices and resources that strengthen the capacity of other groups—such as families, students, and community partners—to participate in collaborative school-site governance. These practices could include making interpretation available for meetings, cocreating linguistically accessible and inclusive meeting materials, and doing targeted outreach to specific groups (especially those who have been historically underrepresented or may be wary of district decision-making).

Spotlight on Practice

Since 2011, OUSD’s Office of Student, Family, and Community Engagement has provided targeted support to community school sites to strengthen the participation of historically underrepresented families in the process of developing Local Control and Accountability Plans. The district’s dual-capacity training builds families’ capacity to understand and participate in school budgeting and governance as well as staff’s capacity to create and sustain collaborative structures. The process includes data training and literacy for families and staff as well as scaffolded agendas that allow for more robust, collaborative participation.

Create coherence in district leadership and organization. In developing a comprehensive whole child approach to student learning, community schools incorporate an array of programs, policies, and practices that are often aligned with distinct district departments—for example, mental and behavioral health services, afterschool programs, career and technical education, and community partnerships. To move beyond what may simply be an “add on” of siloed programs, the district must explicitly work to bring coherence to the varied programmatic elements of community school implementation. The district must actively disrupt and address fragmentation to create a “shared depth of understanding about the purpose and nature of the work.”8

A community school district can foster coherence by considering how and where to locate community school “work” within and across the organizational structure. All too often, community school initiatives are delegated to a single individual or department (such as the Office of Community Partnerships) that rarely has deep influence over the district’s core teaching and learning priorities. Successful community school offices are deliberated and developed in consultation with a wide array of district leaders and teams to best reflect how a community school strategy should strengthen connection and interdependence of the differentiated work across departments. Even if one individual or team is responsible for the core aspects of community schools, the vision and operationalization of the community school strategy must be held collectively and collaboratively by teams and individuals across the district central office.

Spotlight on Practice

One of the most important strategic decisions made in OUSD early in its community school development process was to reorganize the central office, putting all of the community-school-related and whole child functions (e.g., afterschool, behavioral health, restorative justice, social work, family engagement, attendance, and summer learning) under one umbrella, the Office of Community Schools and Student Services (CSSS). The reorganization allowed for greater horizontal integration and coherence, as the various groups within CSSS now hold regular meetings and report to one executive leader. The director of the department is considered a cabinet-level position, which ensures that community schools have a constant presence in cabinet-level conversations.

Strategic Partnerships

Community-based partnerships are a critical ingredient of community schools. These partnerships provide and align resources to support students’ success. In practice, school– community partnerships are often complex and at times challenging because they involve distinct organizational cultures, accountability systems, and perspectives.9 Brokering, managing, and sustaining collaboration across organizations takes dedicated staffing, labor, and time.

Cultivate equitable partnerships at scale and attend to partner management. The district is uniquely positioned to cultivate partnerships at scale, across individual and multiple schools. Larger institutional partnerships—such as the county Department of Health and Human Services, health clinics and health care providers, institutions of higher learning, local businesses, and large nonprofit organizations (e.g., YMCA or Boys & Girls Clubs)—are particularly appropriate for brokering and sustaining at the district level. These kinds of institutional partnerships can provide substantive resources to sustain community schools, such as funding, professional expertise, and human and political capital. For example, during the first 10 years of OUSD’s community school initiative, public and private partnerships provided more than $400 million in funding for school-based services.

Substantive administrative support, from the mundane to the strategic, is needed to broker and maintain partnerships. Partnerships often require legal contracts, such as service agreements, memorandums of understanding (MOUs), facility-use agreements, data-use agreements, and insurance reviews. The district can ease this burden by supporting school sites with the administrative aspects of partnership development. Some nonprofits or CBOs—especially smaller organizations, which are more embedded in the community and can better meet the nuanced needs of the student population and represent students, families, and the community—may need support or guidance meeting district requirements when they have limited administrative infrastructure.

When the district plays a role in managing partnerships, it can also support more equitable partnership development and distribution—that is, help to ensure that partnerships are not concentrated at particular school sites that happen to have greater administrative capacity or relational capital.

Codify norms and best practices for partnership. Community school districts are faced with challenges associated with integrating distinct organizational cultures, accountability systems, and perspectives,10 which can only be overcome when districts see partners not as just vendors or service providers but rather as valued collaborators. Districts can manage partnership expectations by codifying norms and best practices of what meaningful collaboration looks like across the district. This can take the form of giving orientations to new partners, developing tools and rubrics to evaluate partnerships, and writing sample “letters of agreement” to facilitate thoughtful, strategic conversations and planning. All of these support efforts can help ensure greater transparency and stronger alignment between partners and schools, ultimately leading to the potential for braiding resources, meeting the needs of all parties, creating a deeper partnership, and maintaining sustainability of services.

Spotlight on Practice

OUSD employs a district-level community partnerships manager who supports the partnership process and who works in coordination with the community school managers11 to support partnership processes at both the site and district levels. The district partnerships manager removes a major administrative burden from school sites, as central office staff assist with administrative tasks like checking for insurance coverage and ensuring completion of MOUs. The community partnerships manager also provides resources to support partnership alignment at the site level, such as conversation guides, best practices rubrics, and sample letters of agreement, ensuring that partners maximize their impact. Community partners have remarked that they chose to work in Oakland because of the staffing infrastructure that supports community partnerships.

Professional Learning Opportunities and Continuous Improvement

Implementing a community school strategy requires cultivating and strengthening staff’s and partners’ capacities, mindsets, and skills to support a whole child approach to teaching and learning. This capacity building can include training in meaningfully engaging with families, strengthening community-connected learning, and integrating restorative practices in the classroom. The district plays a critical role in creating professional learning opportunities that support the systematic development of community schools’ capacities across the district ecosystem. Effective professional learning opportunities are embedded, continuous, and linked to student learning.12

Develop strong community school coordinators and leaders. Community school coordinators (CSCs) function as high-level school administrators, working with the principal and the school’s leadership team. CSC core functions often include building relationships with partner organizations, managing and integrating partnership resources to maximize impact, strengthening the capacity of staff to meet students’ whole child needs, developing and integrating partnerships, contributing to the coordination of services, and identifying opportunities to engage students, families, and partners in partnership, shared leadership, and voice.13

As a newer role in most schools, CSCs often need help understanding and articulating their responsibilities; principals also need to understand how to best leverage the leadership of CSCs. The district can actively support CSCs and principals by providing explicit, consistent guidance on the CSC role: develop a clear job description, support development of the CSC’s annual work plan, scaffold shared priorities and goals across sites, and create opportunities for cross-site learning, such as in a regular professional learning community. For CSCs to be effective, they must have access to information about district-level initiatives, connections to district leaders, and training on district systems (e.g., enrollment, data, and parent communication platforms) to help them align their work to district priorities as well as take a leadership position and support their site principal.

Embed community school learning within existing professional development infrastructure. Existing capacity-building structures and schedules should reflect how community school values, mindsets, and capacities are developed across sites. For example, orientation of new principals could include a learning session on the community school vision and values, collaborative leadership, and family-partnership strategies. Staff professional development days could include training on restorative practices or community-embedded learning. Principals can be supported to incorporate training on community school practices into teacher collaboration time and site-level professional development. Professional learning should not simply focus on the capacity of teachers or educators but, when possible, should also include learning opportunities for students, families, and partner organizations.

Identify and celebrate community school practices. As community school sites innovate and develop successful practices, the district can play an important role in codifying and systematizing those practices. Professional learning spaces, like communities of practice involving peer schools or roles, can facilitate cross-site learning on emergent practices that have been adapted to and successful in specific site contexts. Seasoned community school districts can offer annual learning forums within the district where sites share their innovations, successes, and lessons learned. The district can learn from and help scale innovative practices developed by school sites.

Spotlight on Practice

At the start of the school year, Oakland’s district-level community school leadership coordinator works with site-level CSCs to develop their annual work plans, which provide the basis for coaching throughout the year. The specifics of district coaching vary by school and the needs of individual CSCs. For school sites new to the CSC role, these coaching meetings can be instrumental in setting expectations and defining priorities. For seasoned CSCs, the meetings provide a helpful sounding board to refine plans and give CSCs up-to-date information about district resources. In addition to coaching support for the CSCs, the district provides coaching for other school roles, such as coordination of services team (COST) leads and student-attendance liaisons.

Scale innovation. As school sites develop innovative practices that work, the district can support the codification and replication of those innovations, such as by standardizing a toolkit for COSTs or replicating successful family math nights. When the district encourages innovation from within, it signals that it values the talent and expertise of its own people, which builds internal leadership and capacity.14

Build on existing assessment, learning, and feedback opportunities. Many districts already have systems and structures in place for continuous learning and improvement. These may take the form of instructional rounds, communities of practice, teacher collaboration time, or other collaborative reflective spaces that use student data to inform practice improvement. The district can leverage these spaces to engage with community school learning and capacity building—for example, instructional rounds focused on community-based learning or family- partnership data dives. It is important that these spaces create opportunities for authentic learning, engagement, and feedback.

Spotlight on Practice

In OUSD, several innovations that emerged from one community school have propagated across the district. For example, the COST was initially developed in select community school sites and has subsequently spread across all OUSD school sites. The district has developed a “COST toolkit” for schools, including job descriptions for the COST coordinator, tips on sharing data and maintaining confidentiality, sample agendas, and rubrics to measure success.15 Other piloted community school innovations include Academic Parent–Teacher Teams and a Parent–Teacher Home Visits program to support meaningful family–school partnerships, positive behavioral intervention systems, and flagship social-emotional learning practices.

Data Systems

Districts can support community schools’ development by ensuring that district data systems and practices support improvement and transparency as important tools to foster whole child, whole family, and whole community collaboration. Reflecting on data together is an important practice of community school partnerships so that school and community stakeholders can better understand, for example, students’ strengths, challenges, and barriers.

Use measures that reflect the whole child, whole family, and whole community. Data should go beyond simply the “satellite” data of state-reported measures (e.g., test scores, attendance, and suspensions) to include tools that give more nuanced measures of school culture and climate or that center student and family voices (e.g., data from surveys or focus groups). With the support of partners, the district can track and use student health and wellness indicators, program participation (e.g., via afterschool, leadership opportunities, and summer learning), and family-engagement data.

Provide accessible, responsive, and timely data. School sites need timely and actionable data, especially as they set priorities and measure progress. It is particularly important that a district’s data platform considers access for CSCs and community partners and ensures that coordinators have the tools they need to use data effectively (e.g., for ongoing assets and needs assessment as well as for site-level continuous improvement).

Negotiate data access across systems. The district plays an important role in negotiating data-use agreements for linking and sharing data across institutions while respecting the protections of each institution and student; for example, it can link student-referral data to services received by site-level providers or obtain aggregate data on student health outcomes from a local health system partner.

Sustainable Resources

Community schools require substantive time and effort to develop; without a long-term sustainability plan, even the best laid plans risk extinction, especially when they are tied to time- limited grant funds. The district plays a critical role in securing and sustaining resources to support community schools.

Districts must consider sustainability from the outset as community schools are often funded by time-limited grants. The relationships that the district builds with institutional, organizational, and municipal partners can precipitate long-term commitments that extend beyond the life of a particular grant. When partner agencies are engaged as authentic collaborators and coconstructors, they are more likely to maintain sustainable resource commitments like funding, staffing, and advocacy.

Districts can support sites by anticipating grant end dates and blending and braiding funding at both the district and the site level. Districts might consider how Title I funding could sustain the CSC position or how health partnerships could be funded through Medicaid. Additionally, districts should map and align the funding streams that support whole child education (e.g., California’s Expanded Learning Opportunity Program and Universal Transitional Kindergarten) and understand how these resources can sustain community school practices and functions.16

Districts should prioritize working with sites to ensure that funding for the CSC role can be sustained. Some districts have moved towards a cost-sharing arrangement with school sites where in the first year of community school funding, the district covers 100 percent of the cost of the coordinator, with sites absorbing up to 25 percent of the cost in subsequent years.

Spotlight on Practice

OUSD’s approach to scaling up its community school initiative began with an application process. Sites were invited to opt in and asked to identify their existing priorities and how they thought community schools could strengthen their work, how they might leverage the leadership of a CSC, and what excited them about the possibility of becoming a community school. Sites were also asked to commit to upholding the values of community schooling as well as to absorbing an increasing percentage of the cost of the CSC. Aligning community schools with existing priorities and fiscal planning from the get-go have helped sites engage with community schools as a long-term strategy rather than a finite grant-funded program.

Conclusion

Districts have an important leadership responsibility to develop the conditions, capacities, and resources for effective, sustainable community schools. Such commitments must run deeper than time-limited grant program activities. Instead, districts must strengthen system- level supports and infrastructure to ensure sustainable resources, shared governance, robust and usable data systems, and organizational learning and improvement. California’s investment in scaling community school strategies across the state provides an important opportunity for districts to organize their resources and strategies to support coherence and sustainability and, fundamentally, to pursue an effective and more equitable way of “doing school.”

- 1The CCSPP is one of multiple whole child funding streams, including Universal Transitional Kindergarten, the Expanded Learning Opportunities Program, and the Child and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative, allocated in fiscal year 2021–22.

- 2California Department of Education. (2022). California community schools framework [Microsoft Word document]. cde.ca.gov/ci/gs/hs/documents/ccsppframework.docx

- 3McLaughlin, M., Fehrer, K., & Leos-Urbel, J. (2020). The way we do school: The making of Oakland’s full-service community school district. Harvard Education Press; Klevan, S., Daniel, J., Fehrer, K., & Maier, A. (2023). Creating the conditions for children to learn: Oakland’s districtwide community schools initiative. Learning Policy Institute. doi.org/10.54300/784.361

- 4The Community Schools Forward task force also produced a theory of action, a costing tool, an outcomes and indicators tool, and a technical assistance needs assessment report for community schools.

- 5Oakes, J., Maier, A., & Daniel, J. (2017, June 5). Community schools: An evidence-based strategy for equitable school improvement. Learning Policy Institute. learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/community-schools-equitable-improvement-brief

- 6Sarikey, C. (2022). Community schools: A journey for collective success. Community Schooling, 2. communityschooling.gseis.ucla.edu/journal-issue-2-policy

- 7Kang, R., Saunders, M., & Weinberg, K. (2021). Collaborative leadership as the cornerstone of community schools: Policy, structures, and practice. UCLA Center for Community Schooling.

- 8Fullan, M., & Quinn, J. (2016). Coherence: The right drivers in action for schools, districts, and systems. Corwin.

- 9Fehrer, K., & Leos-Urbel, J. (2014). Integrated services and supports in Oakland Community Schools [Knowledge brief]. John W.

Gardner Center for Youth and Their Communities. files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED573283.pdf - 10Fehrer & Leos-Urbel, 2014.

- 11OUSD uses the title community school manager; other districts and schools might refer to the same role and functions as the

community school coordinator, director, or resource manager. - 12Desimone, L. M. (2011). A primer on effective professional development. Phi delta kappan, 92(6), 68–71; Darling-Hammond, L.,

Hyler, M., & Gardner, M. (2017, June 5). Effective teacher professional development [Report]. Learning Policy Institute.

doi.org/10.54300/122.311 - 13Tognozzi, N., & Fehrer, K. (2019). The role of the community school manager. John W. Gardner Center for Youth and Their Communities.

- 14Fullan & Quinn, 2016.

- 15Bedrossian, K., & Thomas, V. (2019). Readiness to learn: A school-based model for strengthening health and wellness supports for students. Prepared by BRG for Alameda County Center for Healthy Schools and Communities. brightresearchgroup.com/wpcontent/uploads/2019/08/Readiness-to-Learn-Progress-Report_FINAL_8.14.19.pdf

- 16For more on community school financing, see Deich, S. (with Neary, M.). (2022). Financing community schools: A framework for growth and sustainability. Partnership for the Future of Learning. communityschools.futureforlearning.org/assets/downloads/Financing-Community-Schools-Brief.pdf