Declining Enrollment, School Closures, and Equity Considerations

Summary

Declining student enrollment is leading to a loss of revenue in many California school districts. To address ongoing budget shortfalls, many districts have consolidated or shuttered schools, and others are contemplating doing so. In this session, Carrie Hahnel (PACE/Bellwether) and Francis A. Pearman II (Stanford Graduate School of Education) will discuss new research exploring the racial dimensions of school closures and how to address them. Pearman will discuss a newly released PACE report, Centering Equity in the School-Closure Process in California, showing that closures are far more common for schools that serve higher proportions of Black students, and Hahnel will situate these disparities within the U.S. history of segregation, neighborhood disinvestment, and gentrification, and provide evidence and suggestions to help education leaders center equity as they confront declining enrollment-related school closures. In this session, Carrie Hahnel (PACE/Bellwether) and Francis A. Pearman II (Stanford Graduate School of Education) will also discuss their new policy brief, “Declining Enrollment, School Closures, and Equity Considerations,” which explores the racial dimensions of school closures and how to address them. The researchers will be joined by Tomasa Dueñas (California State Assembly) who will provide a perspective on how state policymakers are tackling this critical issue.

This publication is part of a three-piece PACE series that examines racial disproportionality in school closures in California in the wake of declining student enrollment. In addition to this piece, there is a report and a working paper.

Introduction

Enrollment in California public schools has declined 6 percent since 2007, and it is projected to fall even more steeply over the next decade. At the state level, this decline is largely a result of falling birth rates, out-of-state migration, and shifting immigration patterns. Yet some school districts have experienced more pronounced declines as families have moved from high-cost areas to more affordable parts of the state or have left traditional public schools for other settings like charter schools, private schools, and home schools. Because school districts’ funding is based primarily on average daily attendance rates, a decline in enrollment results in a loss of funding.

There are many ways districts can reduce programs or services, but they can only operate severely underenrolled schools for so long before the situation becomes financially untenable. This is because there are fixed costs associated with operating school sites, including maintenance, utilities, custodial services, and administration, as well as the need to maintain teaching staff to serve the full range of grade levels and student needs. On a per-student basis, underenrolled schools are simply more expensive to maintain. To address ongoing budget shortfalls and align services with student enrollment, many districts have consolidated or shuttered schools, and others are contemplating doing so.

Although school closures may help districts rightsize their budgets and achieve long-term fiscal sustainability, families, educators, and other affected stakeholders commonly contend that closures disproportionately affect students of color, particularly Black students. Despite compelling anecdotal evidence and several high-profile cases of school closure that have garnered significant media attention,1 the empirical literature about the racial dimensions of school closures and how to address them has been limited.

Two new reports, summarized in this brief, help fill that gap. Pearman, Luong, and Greene2 explore racial disproportion in school closures, both in California and nationwide. They find that closures are far more common for schools that predominately serve Black students and that these elevated closure rates cannot entirely be explained by the conventional reasons for why districts close schools, such as enrollment declines and poor achievement. Hahnel and Marchitello3 situate disparate closures within the U.S. history of segregation, neighborhood disinvestment, and gentrification. They provide evidence and suggestions to help state and local education leaders center racial equity as they confront school closures caused by declining enrollment, especially as they relate to racial disproportion.

These reports come on the heels of recent state-level activity addressing the inequitable impacts of school closures. In 2022, Governor Gavin Newsom signed into law a bill requiring that districts, if in fiscal distress, perform an “equity impact analysis” before approving the closure or consolidation of a school.4 In April 2023, Attorney General Rob Bonta issued guidance declaring it “essential that school closure decisions comply with federal and state civil rights laws.”5

This brief begins by summarizing key findings from the research. It then offers recommendations for what local leaders can do to ensure that closures, when needed, are managed equitably. Finally, it recommends ways that state leaders can help support data- informed, equitable decision-making related to declining enrollment and school closures.

School Closures Disproportionately Affect Black Students in California

Between 2012 and 2021, nearly 700 schools across the state were closed, resulting in roughly 167,000 students being displaced. Black students were more likely to experience school closure than any other racial subgroup. Although they represent 5 percent of the total student population, Black students represent nearly 14 percent of the student body in schools that were closed.

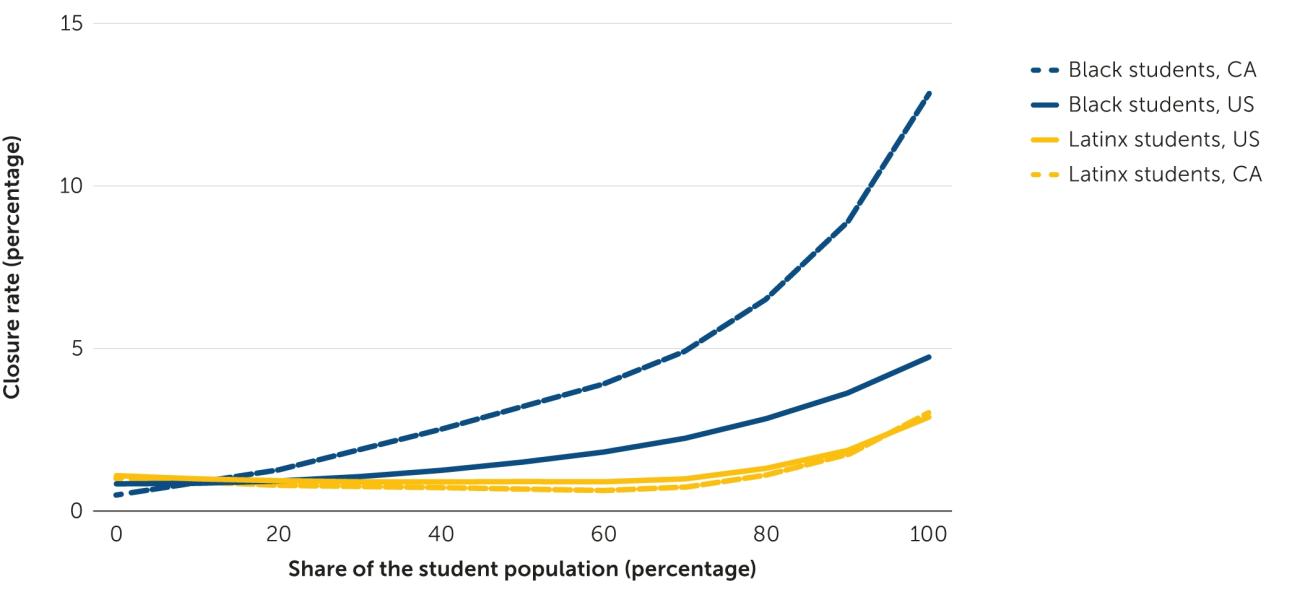

This is happening because schools enrolling larger concentrations of Black students are at increased risk for closure. Pearman, Luong, and Greene used panel data from 2000 to 2018 to show that as the proportion of Black students increases, the rate of school closure also rises. This is truer in California than in the nation as a whole. Figure 1 depicts this relationship. It shows that schools with few Black students—those where less than 20 percent of students are Black— close less than 1 percent of the time. However, closure rates in California climb as the share of Black students increases. For instance, schools with more than 80 percent Black enrollment have about a 10 percent rate of closure—meaning one out of every ten predominantly Black schools close in California, which is more than twice what is observed for these schools nationally.

Figure 1. School-Closure Rates by Student Racial Composition, 2000–18

What Explains This Racial Disparity in Closure Rates for Black Students?

Pearman, Luong, and Greene used inferential analyses to isolate explanations for closures. Focusing on factors commonly thought to contribute to school closures, they found that low achievement, school poverty rates, district enrollment trends, district proportion of charter schools, and district per-pupil expenditures were together unable to explain racial disparities in closure rates. After controlling for all of these factors, they found that schools enrolling higher percentages of Black students were still more likely to close. For example, when the authors compared two schools that were otherwise equivalent in terms of charter status, achievement levels, urbanicity, poverty rates, and enrollment trends and that were situated in similar districts in terms of per- pupil expenditures, total enrollment, and level of school choice, the odds of closure increased by nearly 25 percent for every 10-percentage-point increase in the share of Black students.

Even though the researchers could not fully account for the disparate rates of closure of predominately Black schools, Pearman, Luong, and Greene as well as Hahnel and Marchitello identify several contributing factors. For example, urban schools nationwide and charter schools, specifically in California, are more likely to close than other schools. Urban schools disproportionately enroll students of color and economically disadvantaged students, and schools in those geographic areas experienced a greater enrollment decline between 2012 and 2021. It is also the case that Black students disproportionately attend charter schools, that charter schools are disproportionately located in urban areas, and that they are more likely than traditional public schools to be closed. These urbanicity and charter-status factors may compound to place Black students at an increased risk of school closure. But again, these are only contributing factors—they cannot fully explain the stark racial disproportion in school closures.

Why Practitioners and Policymakers Should Be Concerned About Racial Disparities in School Closures

It is no accident that school closures disproportionately affect students of color. Schools slated for closure are often located in neighborhoods that are currently or were previously underresourced, including neighborhoods that were segregated and redlined during the 20th century. In many of these neighborhoods, including parts of Los Angeles, Oakland, Sacramento, San Diego, and San Francisco, the cost of housing is now skyrocketing. The people who are moving to urban centers are often displacing Black and Latinx families.6 These newer residents tend to have fewer children, and those who do have children often opt out of their local neighborhood schools—particularly if they perceive those schools to be unsafe or low performing. Those perceptions and enrollment choices are often influenced by the racial composition of the school, with White families more likely to avoid schools with larger Black populations.7 The school district may eventually identify these schools as underutilized and therefore potential sites for closure. Indeed, recent research has found that gentrification, specifically the in-migration of affluent households to previously segregated neighborhoods, “was associated with declining enrollment at neighborhood schools.”8 Without thoughtful rezoning following closures, districts risk deepening racial segregation.

Although the decision to close a school can be excruciatingly painful, there is a surprisingly limited amount of empirical research on the impact of school closures on students and communities.9 Moreover, the evidence that does exist is inconclusive. Some researchers have found that school closure results in an initial drop in academic performance, increased negative behavior, and greater absence rates for displaced students.10 Other research suggests that an initial drop in student performance prompted by a closure can be mitigated over time as the initial shock and consequences of the disruption wear off.11 Attending a higher quality school than the one that was closed is critically important to improving students’ achievement after a school closure; unfortunately, districts have typically reassigned students to nearby schools that are roughly similar, academically, to the ones that were shuttered.

How Education Leaders Can Center Equity When Considering School Closures

Given these racial disparities, particularly for Black students, school district leaders must make racial equity a fundamental component of their decision-making when closing or consolidating schools. Although school closures have historically been a matter of local control, state leaders also have a role to play in ensuring that California’s public education system is responsive to statewide demographic trends and equity needs.

To identify next steps and potential solutions, Hahnel and Marchitello conducted a literature review and interviewed practitioners, parent organizers, and policymakers who experienced school closures around the country. This research surfaced recommendations for how local and state leaders can manage closures equitably.

What Local Leaders Can Do

Establish and execute an inclusive and transparent process that engages a wide range of stakeholders:

- Provide ample time and opportunity for community engagement before and during the closure process and ensure there are opportunities for stakeholders to influence the process and result.

- Establish and share clear, values-based criteria that the district will use when identifying schools for closure.

- Share information about demographic and enrollment trends in the district to provide context as well as information about the demographics and characteristics of affected schools, neighborhoods, and students.

- Share information about student growth, achievement, and other outcomes at schools that might be closed and the potential receiving schools, using assessment data that enable meaningful comparisons between school sites.

Implement a strategy to provide displaced students as well as the broader community with accessible, high-quality educational opportunities:

- Reserve and prioritize seats for displaced students in the district’s highest quality schools.

- Provide adequate, accessible, and safe routes to school so that displaced students can attend a high-quality school elsewhere in the district.

- Incentivize effective educators to work in schools receiving a large concentration of displaced students.

- Provide receiving schools with additional resources so that they can offer academic, social, and emotional supports and services to students.

- Repurpose empty school buildings to provide services—such as childcare, extracurricular activity space, and mental and physical health care—that support students and their communities. When leasing or selling surplus property, districts must keep in mind that state law specifies some priorities and constraints for how surplus properties and their proceeds may be used.

- Use school closures as an opportunity to rethink attendance zones and revise school- assignment policies to reduce segregation and create new, more diverse school communities.

Develop and pursue a long-term plan to address factors—such as housing affordability, gentrification, and economic disinvestment—contributing to racial disproportion in school closures:

- Equitably distribute funding and other resources within the district.

- Regularly review population trends, including projections of school enrollment disaggregated by demographic groups, to identify the extent to which the community is attracting and keeping families.

- Collaborate with local governmental agencies, including housing and economic development authorities, to expand and improve affordable housing options for both educators and families and to incorporate the city’s housing element in the district’s facility master plans.

- Work with municipal officials to map out transit plans—including public transportation, bike routes, and walking routes—that provide equitable and safe access to high- performing schools as well as other valuable city services for every family.

What State Leaders Can Do

Study enrollment trends, foster discussion, and generate recommendations for how to rightsize the K–12 education system to align with new enrollment realities:

- Collect and share data on population-level demographic trends and projections, including how these patterns will affect schools and districts. Identify areas where new schools may be needed, where schools may become underenrolled, and where districts could be consolidated.

- Create opportunities for legislative leaders and education stakeholders to reflect on the data and engage in discussions regarding potential solutions. This may include commissioning a statewide review to make recommendations regarding school consolidation and closure with county superintendents, county fiscal overseers, or the state superintendent empowered to act on those recommendations—recognizing that local districts are not always able or willing to close schools, despite the threat of fiscal insolvency. These discussions should include considerations for regional needs and priorities, such as racial and economic integration.

Provide guidance on equity-centered processes for school closure:

- State and county education leaders can offer guidance and support to districts as they navigate the school-closure process. This includes guidance on effectively engaging community members, centering equity in the decision-making process, and using consolidation as an opportunity to address broader teaching and learning priorities.

- Building on existing legislation like Assembly Bill 1912,12 state leaders can encourage all districts to perform an “equity impact analysis” before approving school closures or consolidations. This analysis should consider how closure decisions might disproportionately affect different student groups.

- State leaders can require or encourage policies that give displaced students priority access to preferred schools and high-quality academic opportunities.

To address declining enrollment, incentivize collaboration among school districts, housing authorities, and municipal agencies to ensure thriving and affordable communities for families:

- Incentivize and support local educational agencies to build affordable housing for teachers, school staff, and mixed-income families on surplus district property.

- Promote inclusionary zoning policies and affordable housing policies and programs to help low-income families access stable, affordable housing in areas with quality schools.

- Encourage partnerships between housing agencies and school districts that allow local leaders to pilot solutions that jointly strengthen housing and education in their communities.

Conclusion

In recent years, most California districts have avoided painful decisions about school closures and consolidations thanks, in part, to a large infusion of pandemic relief funding and state hold harmless provisions that have temporarily protected districts from enrollment-related funding declines. These COVID-19 relief funds and hold harmless protections are running out even as enrollments are continuing to decline, costs are rising, and state revenues are flattening. As districts contemplate school closures, they must consider both the evidence and the legal requirements related to equitable impacts. While these new reports serve as a starting point for filling in gaps in the evidence, many more creative ideas and solutions are needed to ensure our public education system responds to new enrollment realities in ways that are equitable and that break segregating patterns of the past.

- 1Bierbaum, A. H. (2018). News media’s democratic functions in public education: An analysis of newspaper framings of public school closures. Urban Education, 53(7), 1045–1070. doi.org/10.1177/0042085918756713

- 2Pearman, F. A., II, Luong, C., & Greene, D. M. (2023, September). Examining racial (in)equity in school closure patterns in California [Working paper]. Policy Analysis for California Education. edpolicyinca.org/publications/examining-racial-inequity-school- closure-patterns-california

- 3Hahnel, C., & Marchitello, M. (2023, September). Centering equity in the school-closure process in California [Report]. Policy Analysis for California Education. edpolicyinca.org/publications/centering-equity-school-closure-process-california

- 4Cal. Assemb. B. 1912 (2021–2022), Chapter 253 (Cal. Stat. 2022). leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=202120220AB1912

- 5Bonta, R. (2023, April 11). Guidance regarding laws governing school closures and best practices for implementation in California [Letter]. California Department of Justice, Office of the Attorney General. oag.ca.gov/system/files/media/letter-school-districts-school-closures-04112023.pdf

- 6Richardson, J., Mitchell, B., & Edlebi, J. (2020, June). Gentrification and disinvestment 2020. National Community Reinvestment Coalition. ncrc.org/gentrification20

- 7Billingham, C. M., & Hunt, M. O. (2016). School racial composition and parental choice: New evidence on the preferences of White parents in the United States. Sociology of Education, 89(2), 99–117. doi.org/10.1177/0038040716635718

- 8Pearman, F. A., II (2020). Gentrification, geography, and the declining enrollment of neighborhood schools. Urban Education, 55(2), 183–215. doi.org/10.1177/0042085919884342

- 9de la Torre, M., & Gwynne, J. (2009). When schools close: Effects on displaced students in Chicago public schools [Research report]. Consortium on Chicago School Research. files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED510792.pdf

- 10Steinberg, M. P., & MacDonald, J. M. (2019). The effects of closing urban schools on students’ academic and behavioral outcomes: Evidence from Philadelphia. Economics of Education Review, 69, 25–60. doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.12.005; Gordon, M. F., de la Torre, M., Cowhy, J. R., Moore, P. T., Sartain, L., & Knight, D. (2018, May). School closings in Chicago: Staff and student experiences and academic outcomes [Research report]. University of Chicago Consortium on School Research. https://consortium.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/2018-10/School%20Closings%20in%20Chicago-May2018-Consortium.pdf; Barnum, M. (2019, February 5). Five things we’ve learned from a decade of research on school closures.

Chalkbeat. chalkbeat.org/2019/2/5/21106706/five-things-we-ve-learned-from-a-decade-of-research-on-school-closures;

Larsen, M. F. (2020). Does closing schools close doors? The effect of high school closings on achievement and attainment.

Economics of Education Review, 76, 101980. doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2020.101980 - 11de la Torre & Gwynne, 2009; Engberg, J., Gill, B., Zamarro, G., & Zimmer, R. (2012). Closing schools in a shrinking district: Do student outcomes depend on which schools are closed? Journal of Urban Economics, 71(2), 189–203. doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2011.10.001

- 12Cal. Assemb. B. 1912 (2021–2022).